If humans are the ones doing the learning, isn’t it inherently human-centered?

Not necessarily. A lot of education is built to optimize the system, not the person: test scores over curiosity, compliance over confidence, performance over wellbeing. Human-centered learning flips that. It treats students as whole people with real lives, real nervous systems, and real agency, and asks a different question—what becomes possible when trust, reflection, and care are the foundation, not the reward?

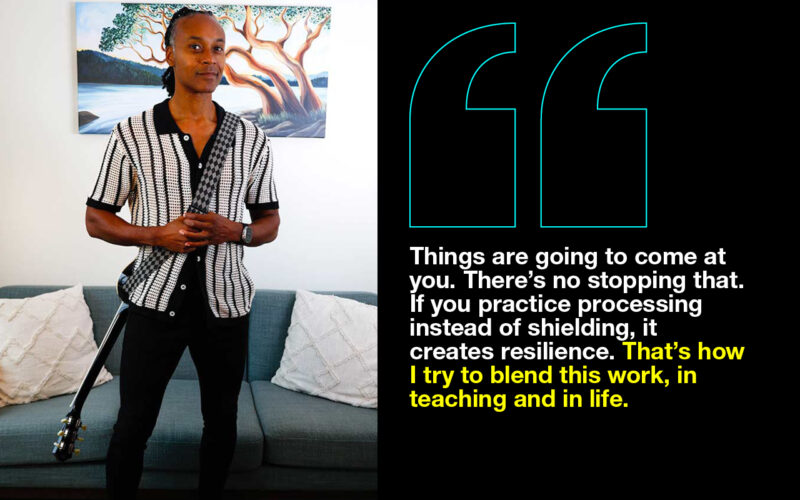

In this Changemaker Q&A, we sit down with Orrett Morgan, an educator and therapist who’s spent decades at the intersection of technology, learning, and mental wellness. From rethinking grading to building “brave spaces” for disagreement, his work challenges the idea that rigor has to feel like pressure, and instead makes a case for learning rooted in self-assessment, relationship, and humanity. Technology, in this model, supports connection—it doesn’t replace it.

I’d love to start by hearing how your work led you to this intersection of technology, wellness, and education.

Yeah, big question. It started in the late ’90s. I was working in a mailroom and I was just tired of it. I’d always loved technology, so I asked HR if I could take on something else. They let me work alongside the IT guy, and I really enjoyed it.

After a while, I got bored again, so I decided to volunteer. At the time I wasn’t married, I didn’t have responsibilities, and I just wanted to get out in the world. I found a program that let me travel to a developing country using my technology and networking skills, so I went to Guyana. I helped build a network at the university there, made cables, and taught people how to do the work themselves.

When I came back, I did different IT jobs around the Vancouver area. But eventually I hit a ceiling. A friend said, “Come check something out at BCIT, they need someone to teach this.” BCIT teaches practical IT skills you don’t always get in a four-year university, so I started teaching there and it was excellent. I basically never left.

Over time, though, I started questioning the way things were being taught. It was very “sage on a stage”: lots of presentations, lots of talking, students regurgitating information, quizzes, all of that. I knew I didn’t want to keep teaching that way, so I did my first master’s in education, a Master of Arts in Learning and Technology, which is really about the pedagogical choices you make when you integrate technology.

That’s where the wellness piece came in. I asked myself: if we actually prioritized educating the human person, what would that look like? The old model prioritizes standardization and the institution, not necessarily the person. And if we’re educating human people, we have to acknowledge we don’t all learn at the same speed or in the same way.

So I started removing what I saw as arbitrary bars and working backwards from the skills people actually need. That led to what we call Teach for Mastery. There are no grades in the program. Students take ownership of what they can take ownership of. If there are four tasks and you can only do one, you submit one. Time, context, situation, biology, all of it matters.

And that’s how it connects to wellness. There’s less stress, less competition. If you can’t do it right now, you can’t do it, and there are usually reasons why.

That’s where the wellness piece came in. I asked myself: if we actually prioritized educating the human person, what would that look like?

You integrate wellness very intentionally into your teaching. What does that look like in practice?

A few years ago, I started integrating wellness much more intentionally. For example, I’ll have students listen to a podcast on vulnerability and shame, and then reflect on it.

The reason is simple: if you go to work without any awareness of what’s going on with you internally, and you think that has nothing to do with your work or what you produce, I think you’re mistaken. Life doesn’t pause because you have a deadline. You might be caring for an elderly grandparent. You might lose a pet. You might go through a breakup. A lot can happen, and you still have to show up.

So we talk about that. If we recognize that human beings have both objective and subjective needs, we also have to get better at naming what’s happening: Why am I having difficulty right now? What do I need? What can I communicate? Do I need rest? Do I need help?

Those questions usually aren’t centered in education. In my classroom, they are.

You’ve spoken about encouraging healthy disagreement. How do you create space for that?

One of the things I do at the beginning is create what I call a “brave space.” A classroom can’t be made fully safe for discourse. People are going to say things.

So we start with a fundamental understanding: we’re not going to attack anybody. If you say something that causes someone else to feel a certain way, you can apologize, you can repair, and you can take ownership.

We call it controversy with civility. It’s okay if we disagree, but how we disagree really matters. We can disagree on the merit, the facts, the ideas, instead of “I don’t agree with this and you’re also a bad person.”

Everybody deserves respect. Nobody has to earn it.

And I give a simple guideline: if you’re not sure if something is racist, sexist, or homophobic, don’t post it. If you have to ask yourself if you should post it, don’t post it.

You were doing hybrid learning before it became common. What were you trying to make possible and what have you seen it unlock for students?

I wanted to remove the barrier of physically coming here. Some people are out of province. One person’s up north. One person’s in Ontario. So you sign up for the program and you get a laptop. Your tuition pays for it. If you’re not here, we ship it to you. That means I know you have a computing resource that can do all the things we ask you to do.

And the other piece is who that brings into the room. People show up with different perspectives based on age, culture, experience. Even the type of question they ask is shaped by what they’ve lived through. That happens every day, and I think that’s inherently a benefit.

People show up with different perspectives based on age, culture, experience. Even the type of question they ask is shaped by what they’ve lived through. That happens every day, and I think that’s inherently a benefit.

What barriers still exist that you can’t fully remove?

One is privilege. You still need power and high-speed internet. That’s a barrier I can’t affect.

The other is financial. Education costs money. It’d be nice if it were free, but that’s the system we’re in.

How has the rise of AI changed your approach to teaching?

As soon as November 2023 came along, that was a paradigm shift. If you’re not using this tool, you’re going to get left behind. We’re training it to get rid of you. Let’s be honest. But it’s like Google was. It’s another quantum leap. You can talk to it like another person. It can guide you. I describe it as a Swiss army knife. It can be a scalpel. It can be a hammer. But you need to learn how to use it.

How do you assess success beyond technical skill?

I train students to self-assess. Because if you always wait for someone else to tell you if something is good, that’s a problem.

The requirement is that you submit something relative to your skill level and take ownership of it.

It’s not about right or wrong. It’s about competency.

Failure is critical. There’s no success without failing. We normalize it.

Self-assessment is key. Trusting self is key.

Your work sits at the intersection of therapy, teaching, and technology. What are you hoping students carry forward from that mix?

Yes, absolutely. My background in therapy influences my teaching, and vice versa. I use technology heavily in therapy for note-taking so I can stay present. If I had to stop and write notes, it would take me out of the session. For me, technology increases my presence rather than reducing it.

Looking ahead, I tell students to find where they add value. Any job that deals only with information is in danger. Where does your human input still matter? Customer service. Support. Human connection still has value. That’s shrinking, but it’s still there. And that’s the best we can do.

And I’ll add this: things are going to come at you. There’s no stopping that. If you practice processing instead of shielding, it creates resilience. That’s how I try to blend this work, in teaching and in life.

At a moment when education, work, and technology are all shifting at once, Orrett’s approach is a reminder that “future-ready” is about building learning environments where people can stay human. Environments where barriers are reduced, reflection is normal, and failure is treated as part of mastery, not proof of inadequacy.

Because in the real world, technical skill and emotional resilience are intertwined. You can’t separate performance from what’s happening in someone’s life, their nervous system, or their sense of belonging.

So the question this conversation leaves us with is practical and urgent:

What would change if more institutions were built for how humans actually learn, struggle, and grow?

QUESTIONS WORTH SITTING WITH :

Change the questions you ask.

Shift everyday check-ins away from results and toward reflection. Questions like “What felt hard today?” or “What did you learn about yourself?” invite agency, context, and honesty instead of performance.

Make failure visible and survivable.

Talk openly about something that didn’t work, moved slowly, or fell apart this week, and name what it taught you, so learning is framed as a process, not a pass/fail outcome.

Interrogate the systems you’re part of.

Look at one classroom, workplace, or routine and ask who it’s optimized for, who it quietly exhausts, and where a small amount of flexibility could make it more human without lowering the bar..