White Bud-tenders Cash In On Black & Brown Incarceration

I vividly remember the first time I walked into a dispensary. I saw a white man, wearing a suit, pull a black credit card out of a designer wallet to purchase some sort of weed product. I walked out without buying anything, angry to my core, thinking about a non-white friend I had in middle school, 15 years ago, who went to juvenile detention for selling marijuana. This wealthy white man’s experience in that dispensary perfectly highlighted just how far removed the modern drug purchasing experience is from the history—and modern realities for BIPoC—of drugs, law, and criminality.

Marijuana, legal today, is inextricably linked to a long history of racism in American drug policy, the war on drugs, and the resulting era of mass incarceration. President Richard Nixon was the first to call for a ‘war on drugs’, though Nixon’s war was largely rhetorical, with little to no policy change occurring during his time as President. When Ronald Reagan came into office in 1981, he enacted policy that brought the rhetoric of the previous administration to life, beginning what we have come to know as the war on drugs.

Since the 1980s, the number of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons has grown from 300,000 to well over two million. While this increase is overwhelming, it’s the racial dimension to it that is perhaps the most horrifying.

Currently, the U.S. incarcerates a larger percentage of its Black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid. Black women are twice as likely as white women to be incarcerated and one in three Black men will be sentenced to prison at some point in their lives, with a higher likelihood of being incarcerated than going to university.

Having lived in the United States, the war on drugs and resulting mass incarceration have made me critical of the U.S. government. However, researching this article reminded me that governments are not homogenous institutions.

Danesh Tandon (who goes by Dan), a San Diego criminal defense attorney (CDA) who has practiced since 1999, is a great example of someone in government who is very much a part of the collective anti-oppression movement.

Dan discovered his passion for criminal law in law school. In criminal law, there are really only two avenues to pursue: prosecution or defense. In Dan’s words, “one side looks at people and tries to find the worst thing about them and highlight it, and the other side tries to find the best thing about people and highlight that, and I much prefer the latter.”

Marijuana was, in essence, criminalized across the US in 1937 with the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act. California, however, was one of the earliest states to begin the decriminalization process with the passage of the Moscone Act in 1975, which made possession under a certain amount a civil, rather than criminal, offense. In 1996, the state legislation passed Proposition 215 which legalized the use, possession, and cultivation of marijuana for medical purposes. In 2003, Proposition 420 was passed, allowing for the creation of medical marijuana ID cards, as well as California’s first dispensaries. Finally, in 2016, Proposition 64 passed, legalizing marijuana for all adults over the age of 21.

In San Diego, Dan’s tenure as a CDA coincided with that of Bonnie Dumanis, a lawyer whose long career included roles as Deputy District Attorney, judge, then District Attorney. Dumanis is known for starting San Diego’s first Drug Courts and for her hardline stance on drugs in California.

Consequently, Dan has had a lot of experience defending folks with drug charges, and in the visible, less visible, and largely invisible ways drug policing and prosecution has disproportionately impacted racialized communities. As Dan half-jokes, “they call marijuana a gateway drug and I actually agree with that; it’s a gateway to racism in the sense that it was used as an excuse to overly [police] Black and Brown communities.”

In the United States, drug laws can be used as a pretext (a reason that is given to justify a course of action that is not the real reason) for stopping BIPoC drivers and pedestrians, searching people and their homes, and so on. Black folks are still 3.6 times more likely than white folks to be arrested for marijuana possession, but the pretextual searches — even when no drugs are found — lead to arrests not captured by that statistic. Nor does it capture the resulting violence committed by police against BIPoC: Sandra Bland was pulled over for not signaling, Philando Castille and Walter Scott were stopped for broken tail lights. Given the stakes, decriminalization and legalization of marijuana in the U.S. has benefited BIPoC communities most.

California, like many states, legalized marijuana for medical use (Proposition 215 in 1996) before it legalized recreational marijuana for everyone 21 and over (Proposition 64 in 2016). However, even in states where marijuana use has been legalized, there remains an important question: what about those who were convicted while it was illegal and remain in prison? Dan sees this, understandably, as a huge issue, and one that CDAs can play a role in mitigating.

For example, the San Diego County Public Defender Office runs a program called Fresh Start. As Dan describes, it functions “to take a look at prior convictions, especially for laws that have changed, and… correct a person’s criminal records, expunge it, reduce felonies to misdemeanors… [That] has definitely had a positive impact on those who’ve suffered as casualties of the war on drugs.”

As Dan sees it, CDAs are often dealing with someone who has already been wounded by the system and CDAs try to cauterize that wound. Historically, though, CDAs were not able to think about (to continue the medical analogy) post-operative treatment. Programs like Fresh Start acknowledge past harms and try to reduce the scarring.

Dan also tries to be proactive in his approach, and believes CDAs have a place in advocacy, especially for decreasing penalties for drug possession and distribution, and the decriminalization of addiction.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 85 per cent of people currently incarcerated in the U.S. have an active substance use issue or were incarcerated for a crime involving drugs or drug use.

Corrective methods (like incarcerating folks to ‘correct’ substance use issues) are harmful, says Dan, who adds “it’s patently ridiculous. There’s no evidence to support that their plan is working and I don’t know what else to show them other than 40 years of incarceration rates increasing and…addiction rates being at the same or higher levels. [This] doesn’t mean your plan is working; it means the opposite, so try something else.”

On dispensaries, Dan’s perspective is loud and clear. “The main criticism I have about dispensaries is that the people who were prohibited from owning and operating dispensaries were those with felony convictions…I don’t know if there is a direct relation to that particular fact leading to a lot of dispensaries not being minority-owned…It’s been gentrified. So yes, I have a big problem with that because we criminalized drug sales and made it seem in the public consciousness that it’s minorities selling drugs to white people, and it criminalized Black[ness] and Browness in that regard, and then when we legalize it…it’s now framed as ‘ok’ because it’s the white people doing the selling and that infuriates me because that source of wealth and income that has been generated from that business is going exclusively to white people and that pisses me off.”

Dan’s beliefs about the discrepancy in dispensary ownership align with a Marijuana Business Daily report saying more than 80 per cent of U.S. dispensaries are white-owned. Today’s retail marijuana industry is overwhelmingly white — a direct result of the criminalization of marijuana and drug policy and policing choices that criminalized Black and Brown people.

So, what can we do? It is daunting, but there are actions to take. We can find and support programs that expunge or reduce the records of those harmed by the prison industrial complex. In the U.S., nearly half a million people are incarcerated for drug-related offences, and police make more than one million arrests per year for drug possession. To use Dan’s analogy, that’s a lot of post-op that needs to be done.

There are also many NGOs that work towards similar outcomes. The Drug Policy Alliance, the Sentencing Project, and the Last Prisoner Project advocate for policy change at the federal and state levels, and provide support to formerly incarcerated individuals.

Finally, advocates must strive for decarceration (the reduction of the prison and jail populations by means of policy change) and, ultimately, carceral abolition.

The carceral state is not repairable because it is not broken. It is a (relatively) new structure made up of (relatively) new institutions that have an old goal: to reinforce the racial caste system that has defined the U.S. from slavery, to Jim Crow laws, and continues today through the racist enforcement of drug laws. ■

Digital Extras / #CannabisEquity Interviews

Buying drugs these days is far removed from the history—and modern realities for BIPoC—of drugs, law, and criminality. Hear from three changemakers in the industry on the challenges BIPOC face in the cannabis industry and how [the industry] can promote and celebrate diversity.

Purchase Issue 03

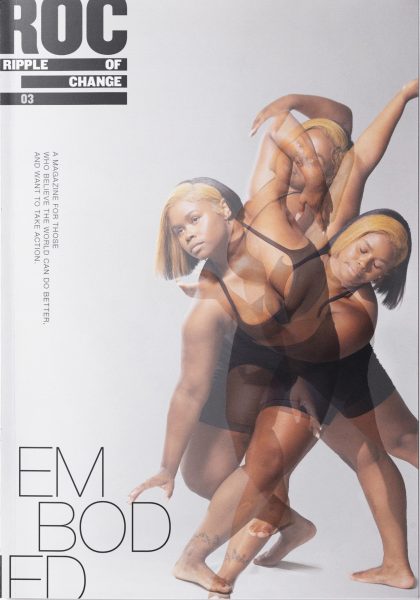

After a year of chaos and uncertainty, our mission for ISSUE 03 of RIPPLE OF CHANGE is to spark inspiration in our readers. There was a lot of talk of coming together, acting in solidarity for our peers, and putting others before ourselves to overcome the challenges put before us. Now, we put that to the test.

Order your copy of Issue 03 today!