We Live in a World That Refuses to See Us

Transphobic laws, bias and outdated healthcare practices prevent trans and non-binary folks from accessing gender-affirming care — but there is hope on the horizon.

Accessing health services often reminds transgender, non-binary, and gender nonconforming people that health systems are not made to include them. For trans and non-binary people, physical, legal, financial, and psychological barriers present an exhausting array of challenges to accessing care. From clinicians needing to be educated on how to provide gender-affirming care, to long waitlists for gender-affirming surgeries, to inadequate insurance coverage, simply walking in and out of a health clinic, unscathed, feels nearly impossible. Thankfully, queer and trans-led organizations, grassroots activists, and medical professionals are getting creative with solutions to overcome these systemic barriers.

Tatiana Ferguson is the co-founder of the Black Queer Youth Collective (BQYC), an organization that provides opportunity and support to Black 2SLGBTQ+ youth living in Toronto. She is acutely aware of the challenges faced by trans and gender nonconforming youth accessing health care. When she sees non-inclusive intake forms at health clinics, she feels frustrated because her work for the gender-diverse community in Toronto has long been centred around making systems more inclusive.

Generally, these intake forms are unclear about what they are asking for and why. For example, forms may ask ‘what is your gender?’ with ‘male’ and ‘female’ as the only two options to answer.

“Is it ‘what sex a person was assigned at birth?’ Is it ‘what is a person’s current gender identity?’” Tatiana wonders, pointing out the lack of competency around gender and sex in cisnormative medical spaces.

Neither sex nor gender are binary categories. To assume sex is a binary erases the experiences of intersex people. Similarly, gender is not limited to ‘man’ and ‘woman’. Both sex and gender can be better thought of as spectrums, with unlimited possibilities and combinations. To complicate matters further, Tatiana says many “organizations use sex and gender interchangeably, which creates issues of confusion.”

With this much confusion about asking the proper questions on sex or gender, one might assume that a question asking what pronouns a person would like to use is uncommon in health clinics.

Neither sex nor gender are binary categories. To assume sex is a binary erases the experiences of intersex people.

– Ace Chan

However, Tatiana says that, in some parts of Canada, “asking someone’s pronouns or checking in about pronouns is normalized,” which provides hope for those who are living in places where this is not the case and misgendering is part of the daily struggle. With the switch to virtual health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, Tatiana says it’s easier to misgender someone when you can’t see the person or if their “voice is lower or higher then they identify.” However, Tatiana did point out that being able to write your pronouns after your name in online health visits allows people to state how they want to be addressed.

Dr. Crystal Beal, founder of an online health clinic that provides gender-affirming care and other services for 2SLGBTQ+ community members, includes a question about pronouns on their intake form. Crystal’s thoughtfulness even goes as far as to removing pronouns from templated notes because if someone is being prescribed estrogen, for example, they might not want to be referred to with she/her pronouns.

Another barrier arises when it comes to interacting with insurance providers. Crystal writes letters to insurance companies so that patients can have their gender-affirming surgeries covered.

“Some insurance companies need us to use pronouns [to] have the patient’s surgery approved,” they explain, which does not necessarily mean those pronouns are gender-affirming. For example, if an insurance company sees a letter for vaginoplasty written for a patient with they/them pronouns, insurance providers may be less likely to approve the surgery than if the letter were written with she/her pronouns. In scenarios like this, patients have to decide whether or not to “go to bat with the pronouns they want to use, which might be a barrier for surgery approval.”

Is gender identity collected in large-scale population health surveys?

Moving out of a clinical setting and into a research setting, this lack of inclusion happens in large-scale population health surveys too. For example, the National Health Interview Survey, developed in the United States to monitor the health of Americans, does not include a question on gender identity. The Canadian Community Health Survey only started including gender identity questions in 2019, after community members and researchers sent numerous policy briefs to the House of Commons.

Most population surveys use random sampling and, in turn, generate results that are representative of the entire population. For example, if each person living in Canada has the same chance of being selected for a study, then the study findings can be extrapolated to determine trends in Canada’s population as a whole. This kind of data is invaluable for researchers aiming to identify health disparities in at-risk or vulnerable communities in a country.

Studies have shown that gender-affirming care is linked to a reduction in suicide ideation, improvement in baseline functioning, and improved mental health.

– Ace Chan

Why is this lack of inclusion such a big deal?

Evidence that demonstrates inequities in health outcomes can drive policy changes or public health interventions. If at-risk groups like trans or non-binary people are not identified in health surveys, they become ‘hidden’ populations and any disparities in care or health outcomes are unknown.

Without good data, advocates and physicians can’t access the resources they need, says Crystal. “You can’t formulate questions for research and apply for funding. You can’t get funded because it’s unclear how many people are affected, since there is no count of what per cent of the population [is] gender diverse.”

“Gender in our community is so expansive,” says Tatiana. “We are doing a lot of work to shift the way we report on gender for trans-specific studies, but this also needs to be modelled by mainstream public health surveys.”

What kind of data is out there?

In the absence of randomly-sampled large-scale population data, researchers and policy-makers rely on community-based health surveys that, despite their limitations, provide insight into health disparities of trans or non-binary communities. The Canadian Trans Youth Survey, Trans PULSE Canada, and the U.S. Transgender Survey are examples of community-based health surveys that offer a picture of health outcomes in these communities.

What do these studies tell us?

From these studies, community members, researchers, and policy-makers have begun to identify issues, such as barriers to accessing care and disparities in mental health outcomes, that affect the gender-diverse community. Through these surveys, Tatiana and Crystal have learned that barriers to accessing care include: clinician incompetency, long waitlists, language barriers, lack of health insurance, distance to care, and fear of being mistreated, among other items.

The worst stories Crystal hears are when their patients have “inappropriately been asked to take their bottoms off when they go in with a head cold,” which they describe as “heart-wrenching.” Within the medical community (and beyond), people are often curious as to what genitals trans or non-binary people have, how they have sex, and who they are attracted to. Needless to say, unless a patient is seeking sexual or reproductive healthcare, these details are rarely relevant. Thankfully, Tatiana thinks there has been a shift toward health care providers being open to acknowledging gender diversity and applying that knowledge to their work, though challenges remain as not all clinicians are open to making their practices more trans-inclusive.

In addition to findings from community-based health surveys, Crystal mentioned that, for people whose gender expression is non-binary, “they have more trouble finding knowledgeable providers because guidelines are written from a binary [perspective], which has left a deficit in health care for people with less binary presentation goals.”

Everyone’s journey is different and it’s important to remember that not all trans or gender-diverse people want to access gender-affirming hormones or surgery — some people may only want access to gender-affirming garments.

Sam Porta runs Bras, Binders, and Breast Forms (BBB), at QMUNITY, a resource centre that serves queer, trans, and Two-Spirit people in British Columbia. The BBB program provides new and used garments, at no cost, to trans and non-binary youth who may otherwise be unable to obtain these items due to cost or lack of support. When it comes to gender-affirming garments, they say there are some common misunderstandings. For example, “certain gender-affirming things like packing or tucking don’t mean it’s a step towards medical transition. For some people it is, but for a lot of people it isn’t,” Sam says.

For gender-diverse people, access to gender-affirming care can create positive mental health outcomes. “Research supports that gender-affirming care saves lives,” says Crystal — a statement that can also apply to youth who receive garments through the BBB program. Crystal says studies have shown that gender-affirming care is linked to a reduction in suicide ideation, improvement in baseline functioning, and improved mental health.

Sam, who runs the BBB program, believes that gender-affirming care is “inextricably tied” to better mental health.

However, Crystal is careful to offer the reminder that gender-affirming care “doesn’t fix everything, as we are not just one thing.” Someone’s mental health can also be affected by anxiety or experiences of trauma, they add.

People must go beyond a rainbow sticker on their door and challenge readers to ‘ask yourself, are you creating a safe space all the time?‘

– Sam Porta

The beautiful moments amidst the chaos

Given the ties between gender-affirming health care and mental health, anti-trans hate and transphobic laws preventing trans or non-binary people from accessing gender-affirming healthcare are worrisome. Bodily control is at the root of many of the arguments governments and institutions use to deny adequate health care to young trans and non-binary folks. As with abortion rights, end-of-life care, and other medical processes, gender-affirming solutions like hormones and surgery are often denied because lawmakers do not respect the autonomy and self-determination of marginalized people. To further this agenda, right-wing media outlets often focus attention on a small number of people who regret their transition while overlooking the many beautiful stories of people who have flourished since accessing gender-affirming care.

When they have access to gender-affirming garments, Sam says that the youth who use the BBB program are “over the moon..ecstatic [and] feel like themselves.”

Crystal reminds us that “gender is an evolving journey and doesn’t mean that different treatments in different directions and routes are wrong at different times [in] someone’s life.”

When asked about her gender journey, Tatiana views her transition very positively and compares the experience with the life cycle of a caterpillar. “Transitioning has been one of the more beautiful experiences I have had in life because I can be my authentic self and that is comforting,” she says.

Health equity and gender-affirming care contribute to so many positive outcomes. While Sam, Tatiana, and Crystal fight for equity in their respective professions, allies still have a role to play to change transphobic systems. ■

Digital Extras / #CannabisEquity Interviews

Four changemakers discuss the biggest barriers facing trans and non-binary folks in accessing care as well how we can support their work. There is hope on the horizon.

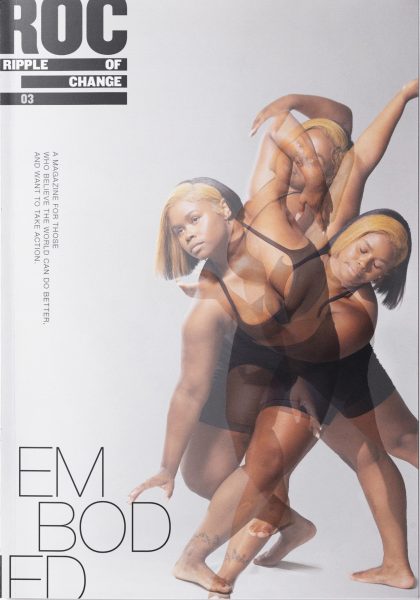

Purchase Issue 03

After a year of chaos and uncertainty, our mission for ISSUE 03 of RIPPLE OF CHANGE is to spark inspiration in our readers. There was a lot of talk of coming together, acting in solidarity for our peers, and putting others before ourselves to overcome the challenges put before us. Now, we put that to the test.

Order your copy of Issue 03 today!