The Movement for Dance Inclusion

Creating inclusive performance spaces

Photography by Xander Sutjiadi

Growing up in Venezuela, Serenella Sol was surrounded by dance – her grandmother and mother both practiced ballet. Movement is in her blood. When she was three years old, Serenella attended her first ballet. Her mother brought her to see a show at the Teatro Bellas Artes in Maracaibo, a 600-seat theatre. That night, she fell in love.

“I remember very clearly, a ballerina in a white tutu coming from the left, her back to the audience. Her arms were moving like water; it didn’t seem real. My three-year-old brain thought she was floating,” says Serenella.

She spent the entire show in awe, totally entranced by what was happening onstage. After the show, Serenella told her mother she wanted to be a ballerina. However, Cabimas, the small city in the northwest corner of Venezuela where she grew up, offered few classes for budding dancers. Seeing her daughter’s passion, Serenella’s mother enrolled her in classes at a dance school a thirty-minute drive away.

During one of Serenella’s first classes, she remembers learning the rond de jambe – a dance move that involves making a half circle with your toe on the floor. She fondly remembers how some of the other kids seemed bored, but she was mesmerized by its simplicity and structure.

Now 33, she has spent 30 years dancing in Venezuela and Canada. Although ballet is technically complicated, Serenella finds that it provides simplicity and comfort in her life.

“You go, you learn something and you can be quiet with your body and just focus,” she says. “When I’m dancing, it’s the only time I’m actually feeling my body fully in the moment because that’s where I’m supposed to be.”

While ballet provides a certain comfort for Serenella, her experience has not always been positive. Over the years, Serenella has experienced toxic culture in the dance world, leading her to step away several times. To pay for college, Serenella needed to work — at times, she had to quit dancing to save money. Many dancers find the cost of dance classes inaccessible. She also found that the pressure for perfection in the art form caused a lot of body-related trauma.

“As a kid, my ballet teacher would weigh us in front of people,” she says. “Thinking back on it, that may be the reason I’m terrified of stepping on a scale. These things shouldn’t happen to a kid!”

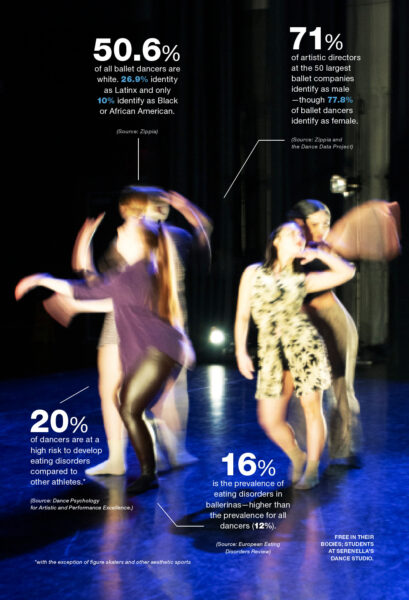

The culture that surrounds dance, especially ballet, can be oppressive. Serenella says that Eurocentric and fatphobic beauty standards, lack of diversity, and high costs can be barriers to participation, resulting in low levels of diversity.

As dance has not always been a safe place for Serenella — both in Venezuela and Canada — she created the safe space she wanted in Ballet Bodies YYC.

Serenella got back into ballet during the first few months of the pandemic. By practising barre – a workout inspired by ballet – at home, she found it liberating to be by herself, with no mirror (or judgment) in sight and she wanted Ballet Bodies YYC to mimic that feeling.

Co-founded in August 2020, in Calgary, Alta., the Ballet Bodies YYC collective aims to create a collaborative, positive, and inclusive space for adult, intermediate, and advanced ballet dancers to train and perform regardless of age, gender, or physique — having participants feel comfortable in their skin is a top priority.

There are signs displayed in the studio, reminding people that it is a safe space. Instructors know to help dancers with technique and not to critique their bodies or abilities. The studio ensures that clients and instructors don’t comment on anyone’s bodies and doesn’t require leotards to be worn — dancers can train in sweatpants if they like!

Ballet Bodies YYC strives to right the wrongs of ballet culture. For decades, researchers have been exploring the challenges faced by dancers, especially those who feel excluded from the art form. Many dancers feel dissatisfied with their bodies and may feel uncomfortable in rooms linedwith mirrors. These compounding factors lead many talented and passionate ballet dancers to quit.

Beyond the ballet world, many people feel pressure to be skinny, look a certain way, or fit into idealized beauty standards that feel unattainable. Today, many social standards of beauty are rooted in sexism and patriarchy, with women, girls, and feminine-presenting people experiencing the brunt of the pressure to conform. Feminist dancers and dance researchers are critiquing these beauty standards.

In American Ballet Theatre: A History, former professional dancer Jennifer Homans says ballet was created “to express masculinity, power, strength, physical precision, control.”

During the Romantic era in the 19th century, painting, music, and dance began to focus more on grace and elegance. With the invention of the pointe shoe, more often worn by women and notoriously painful, ballet shifted from masculine to feminine. Nowadays, we are accustomed to ballet being represented by a thin, white, feminine body in a pink tutu, erasing the dance style’s history and not reflecting its current diversity.

While many ballet dancers are (cisgender) women, a lot of choreographers, directors, and show presenters are men. While dance may seem like a world led by women, much is still dictated by the male gaze. A ballerina is traditionally “a woman made by a man,” says Pam Tanowitz, the only female choreographer at the New York City Ballet.

Body image issues also affect people of other genders. Trans, non-binary, and Two Spirit people struggle with the stringency of conformity in the dance world. Additionally, while cisgender men dominate powerful positions in the dance industry, male dancers, especially those who are not white and slim, face a lot of pressure around their bodies.

Bradley University in Illinois found that men are less severely affected by body image issues in general, but in social situations, the impacts are the same. Men often tend to be quieter about their body insecurities, while women internalize theirs and are more likely to participate in body shaming. Gender nonconforming people are often left out of research on body image, but undoubtedly experience similar impacts, due to the pressures of a patriarchal society.

In ballet, and many other dance styles, the masculine/feminine binary is very stringent, leaving queer, trans, and gender nonconforming performers grappling for inclusion and acceptance. A lot of dance styles mimic social hetero- and cisnormativity by forcing dancers into one end of the gender binary and expecting men to lead in pair or group dances.

“The culture created around these ideas systematically disempowers women by relying on and adhering to actively unfeminist, patriarchal, and paternalistic standards and principles that are, in the end, damaging to people of all genders,” writes ballet dancer Sarah Cecelia Bukowski.

Dance is an inherently expressive form that should allow freedom — which is exactly the inspiration behind Serenella’s work with Ballet Bodies YYC. She is helping a community of adults in Calgary feel comfortable dancing again, in their own skin, and bringing new admirers to the art form. The collective helps her too — through her work, she’s able to be artistic, dance, and make ballet more accessible.

“I feel like, now it makes sense, now I know exactly what I need to do. I’m performing, but I’m also making a positive impact in the community, which is what art should be about anyways.”

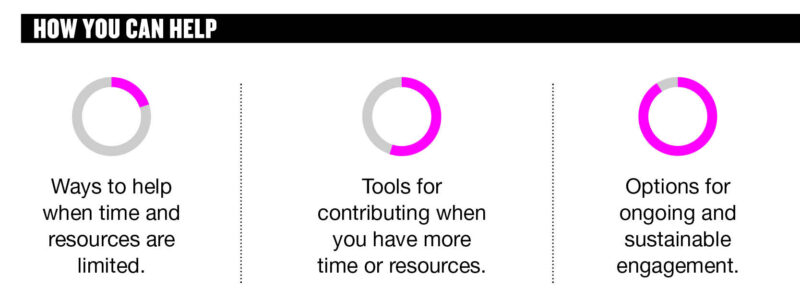

HOW YOU CAN CREATE IMPACT:

PICK UP books like Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia or Dancing In The Streets: A History Of Collective Joy to learn how you can feel more comfortable in your own skin.

Listen to podcasts like the Affirmation Pod hosted by Josie Ong to learn how to silence your inner critic.

Elevate your knowledge by taking courses like the ones offered by The Body Positive or The Fierce Fatty.

Purchase Issue 03

After a year of chaos and uncertainty, our mission for ISSUE 03 of RIPPLE OF CHANGE is to spark inspiration in our readers. There was a lot of talk of coming together, acting in solidarity for our peers, and putting others before ourselves to overcome the challenges put before us. Now, we put that to the test.

Order your copy of Issue 03 today!