Protesting on Nana’s Shoulders & Other Stories of Intergenerational Activism

One of my earliest memories takes place two summers shy of the 21st century. I am on my Nana’s shoulders and we are in a lively crowd of our friends and neighbours, marching along a street in the suburbs of London, England. Our destination is the firehouse; it is big and red and everything my four-year-old self found thrilling in life. We are protesting gentrification; the firehouse, an important part of keeping our community safe, is being turned into fancy apartments. I don’t really understand this of course, and I certainly don’t know words like ‘gentrification’ but I know that Nana is enraged, and therefore so am I.

Moments like this became a staple of my upbringing. Protests, council meetings, opinion pieces in the local newspaper, Labour Party conventions; I am soon intimately aware of, and blissfully optimistic about, my role in the socialist revolution. When the adolescent angst coupled with the harsher realities of sexism and racism knocked my confidence down a peg or two, Nana was there to give me hope — and tools — for change. In grade 12, my final essay discussed the disenfranchisement of Black voters in the U.K. Nana introduced me to her friends at the local anti-racism taskforce she helped found, who provided great insight and inspiration for my writing. Her support on this project, albeit a poorly-cited high school essay, became another anchor in my metaphorical memory box labelled ‘How My Grandmother Made Me an Activist.’

Last week, Nana called me to say she had awakened with the sudden thought that I should run for office. I tried to explain that a Black, queer activist is probably not a top choice for the average Canadian voter, not to mention how difficult it would be to politics-proof my social media presence. Despite how unfeasible the reality is, this vision in her mind is a symbol of the values she has instilled in me throughout my life. Directly and indirectly, the women in my family have passed down the necessary skills, wisdom, and commitment to justice required for the socialist revolution.

My white grandmother, born to a working-class English family in the 1930s, is not your textbook intersectional feminist. I know many people, especially other queer folks, whose family reunions are full of intergenerational antagonism and unresolved trauma. Common experiences of millennials and gen-Zers are uncomfortable dinner table conversations, ongoing emotional labour educating boomers on why respecting pronouns is important, or complete estrangement from family members unable (or unwilling) to move into the 21st century.

My generation is finished, I no longer have any effect on people’s thinking, but young people, of course, can indeed make a huge difference.

– Jean Robertson (Nana)

While these stories are painfully common, they do not have to define our intergenerational relationships. With my immediate family spanning five generations, I am lucky to be related to some pretty rad people, though the terms ‘ancestor’ or ‘elder’ are by no means exclusive to biological families. For many folks — queer and trans folks, immigrants, trauma survivors, orphans, and others — family often bursts out, away from the restrictive bounds of blood relation. I was curious to explore how elders — whether related, chosen, found, or encountered-in-passing — impact the work and lives of young changemakers.

Scrolling through Instagram, I am struck by a series of sweet photos: a small brown-skinned child laughing in the folds of a sari; a chubby-faced baby with a bowl haircut, cheeks smushed between their mother’s fingers; two pairs of eyes peeping over the top of bundles of lush green vegetables. These are the photos that complement #ShareToSustain, a storytelling project by Shades of Sustainability.

Run by a group of young people in Vancouver, Shades of Sustainability is a community project that aims to unpack what it means for racialized folks to engage in environmental action.

“This project is a platform for us, as youth from diverse backgrounds and lived experiences, to redefine sustainability and environmental action,” explains Melisa Tang Choy.

Melisa’s picture is the one with the smiling eyes and fresh vegetables: it is Melisa and her aunt with the green stems of white radishes. Using the tops of radishes as food is unusual — many people throw them away, unaware they are edible. According to the National Zero Waste Council’s research on household food waste in Canada, almost 2.2 million tonnes of edible food is wasted each year. Without knowing it, Melisa’s aunt passed down a sustainable practice to her niece.

This is often the case: practices that were common for previous generations, especially those who grew up poor or in the Global South, became lost as societies adopted mass production and consumption. Arguably, the crux of the boomer-versus-millennial tension revolves around the rampant production and overconsumption of plastic and the glorification of capitalism during the post-war period, particularly in the West.

“Credit cards made people spend to excess; TV and the advertising on television; the introduction of gambling, which many people saw as a way to get rich quick; far more traffic on the road,” my Nana says, listing examples. I asked her how she evaded this titillating period of economic boom and abundance. “I am ashamed to say I didn’t to some extent,” she says sheepishly over the phone, “but I think the war mentality will always stay with me. Austerity and restrictions during the war years altered people’s perceptions and certainly altered the way they lived.”

At Nana’s house, the cupboards are full of 30-year-old cans of beans. Every plastic bag is saved and neatly folded for reuse. The biscuit tins are actually sewing kits or something else disappointing.

“I try not to waste gas and electricity. I try not to waste water. I try not to throw food away,” she says. “I suppose you would call that sustainability now, but it is how I have always lived.”

While a focus on sustainability and eco-friendly practices has become more mainstream over the past few decades, the reality of enacting these practices has become more inaccessible. This is something Shades of Sustainability attempts to combat in their work.

“The systems of capitalism and white supremacy [that] have driven the climate crisis that we’re currently in have also co-opted the movements. These forces have made the [climate justice] movement inaccessible, such as thinking that to be a good activist we need and purchase x, y, and z,” write Melisa and co-organizer Jocelle Refol.

Nana’s generation found unity in their shared struggle. “World War Two was a class equalizer; rations were the same for everyone,” she explains. In contrast, contemporary greenwashing often places the onus on the individual to do their part, ignoring the reality that corporate greed and government inaction are the core drivers of climate change. According to The Guardian, just 90 companies are responsible for two-thirds of the planet’s human-made greenhouse gas emissions.

Not only do more ‘sustainable’ products often cost more, but they are also often made at the expense of underpaid workers in the Global South.

“We felt like so much of environmental justice and sustainability was centred around the Western world and often that discouraged others in our family to get involved because it didn’t seem to be ‘for them’,” write Jocelle and Melisa. “However, many of us know that, with family abroad, especially in the Global South, the impacts of climate change would be disproportionate, but that often isn’t of focus here [in North America].”

All of this strikes me as an incredible opportunity for intergenerational collaboration. “My generation is finished, I no longer have any effect on people’s thinking, but young people, of course, can indeed make a huge difference,” Nana says. There is some irony in this though as America recently elected their oldest-ever President — undoubtedly an intersectional analysis would reveal why.

To this point, I wanted to dive deeper into the impact race and gender have on older generations. I reached out to the Yarrow Intergenerational Society for Justice 世代同行會. Founded as a grassroots organization in 2018, Yarrow supports youth and low-income immigrant seniors living in Vancouver’s Chinatown and Downtown Eastside neighbourhoods. Their mission is to build power in the community through intergenerational relationship building, and help seniors overcome language and cultural barriers to services that meet their basic needs.

In cities across North America, Chinatowns are experiencing rampant gentrification (the same kind my Nana and I marched against many years ago), meaning low-income residents, mom-and-pop shops, and immigrant communities are being pushed out by high-end stores and restaurants. This form of structural violence puts many of Yarrow’s Chinese seniors at risk. In a recent example, the owners of the Grace Seniors Home, which provides homes for low-income seniors, put the building up for sale, leaving residents uncertain about their future.

Beverly Ho, Yarrow’s operations manager, agreed to meet with me to share more about their work. Beverly brought along Ma Xing Jun (馬杏軍), a senior who accesses Yarrow’s programs. Ma Xing Jun is known as Ma Tai, or Mrs. Ma, to most people and, as our relationship developed over the Zoom call, she invited me to call her 阿姨 (ah yee) which means ‘aunty.’ Mrs. Ma is multilingual and often switches between Cantonese, Mandarin, and Shanghainese. My Cantonese is limited to ying guo ren (British person), do ze (thank you), and zoi gin (goodbye), so Mrs. Ma spoke Mandarin and Beverly translated for us.

Mrs. Ma began by inviting me to tea at her home — a small gesture that is a normal custom for her but at odds with my British upbringing. The individualistic focus of the culture I was raised in seldom allows for such a generous invitation to a stranger. I thanked her for the gracious invitation, feeling a warm fuzziness at the thought of sharing tea with an elder for the first time since I saw my own Nana before the pandemic hit.

“I am very happy to know Miss Ho, she has a nice personality,” says Mrs. Ma, “At the time I met her, I was very depressed. My husband was struggling with a lot of health complications but when I met Beverly, I was happier.” She explains that Beverly noticed how frail she was, given her lack of appetite and encouraged her to eat. With her own children living in China, Mrs. Ma enjoys the company and support of Beverly and other young people from Yarrow. “The youth are great, they always listen to me.”

Beverly feels similarly about her relationship with Mrs. Ma. “For me, it’s the intergenerational connection. I get the privilege of learning about my cultural roots… It’s just nice to hang out with someone older and loving, who has a lot to share.”

Melisa and Jocelle at Shades of Sustainability expressed a similar sentiment: communicating with older generations in languages that felt familiar to them was a huge part of their #ShareToSustain project. Asking elders about their stories is “a way to share lessons, pass on knowledge, and preserve culture,” they say.

Mrs. Ma moved to Vancouver in 1982 when she was 50 years old and initially faced challenges finding employment. “When I came to Canada, I cried a lot. I was always crying, because of the language barrier,” Mrs. Ma explains, detailing how she found work by asking fellow bus passengers if they needed a nanny for their children. Eventually, a Taiwanese family offered her employment.

“She has always been a caretaker in [her] personal and professional life,” Beverly says fondly.

Mrs. Ma reminds me a lot of my Nana: both have an infectiously positive outlook on life, despite hardship. In my interviews, I asked each of them if they had experienced ageism and both said ‘no.’ Perhaps a certain resiliency keeps the nonagenarians smiling.

Many conversations among my millennial and gen-Z friends circle endlessly around the doom and despair of our uncertain future. And while the climate crisis will undoubtedly impact us, we must not be naive and ignorant in thinking we are the first generation to experience such fear.

Intergenerational relationships hold their power in preserving language, culture, and stories. Most importantly, these relationships offer tools and strategies to address systemic issues and the hope to continue building livable futures. Whether related or not, our elders are often only a phone call, prayer, or tea visit away, and prepared with simple answers to our biggest questions. ■

Purchase Issue 03

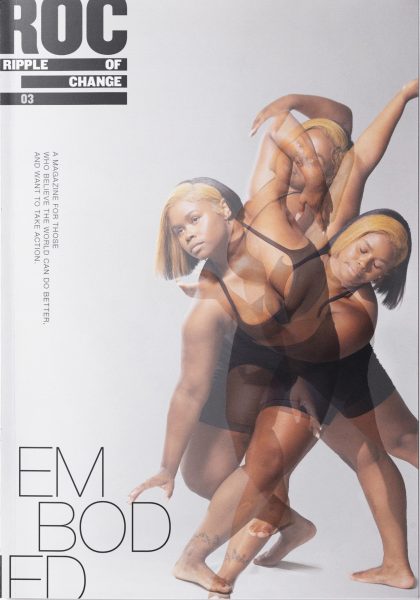

After a year of chaos and uncertainty, our mission for ISSUE 03 of RIPPLE OF CHANGE is to spark inspiration in our readers. There was a lot of talk of coming together, acting in solidarity for our peers, and putting others before ourselves to overcome the challenges put before us. Now, we put that to the test.

Order your copy of Issue 03 today!

Cicely Belle Blain

Editorial Director (they/them)

Cicely Belle is a Black, queer writer, activist and anti-racism consultant originally from London, UK. They are the founder and CEO of Bakau Consulting, a social justice informed equity and inclusion consulting company based in Vancouver, BC where they work with clients across six continents to enhance compassion, respect and a commitment to anti-oppression in a diversity of industries.

As a founder and former organizer of Black Lives Matter Vancouver, Cicely Belle is passionate about liberation work, systems change and radical empathy for a better world. In 2018 and 2020, they were listed as one of Vancouver’s 50 most powerful people and in 2019, as one of BC Business’s 30under30. They are the author of Burning Sugar and an instructor of Executive Leadership at Simon Fraser University.