Long awaited flooding recognition offers truth, reconciliation and a resilient future

When kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation Councillor George Chaffee talks about his mother, his eyes light up and he swells with pride. He explains that the only reason slakəyánc (IR1), the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm territory, 6.5 acres situated on the bank of the Coquitlam River in British Columbia, Canada has survived over 200 years in a floodplain is because his mother, Chief Evelyn Joe, Kwikwetlem’s first female chief, challenged the government in the 1990s and put herself on the line to protect her people.

“Flooding in our community has been a serious issue for several decades now due to rising levels of water from the Coquitlam Lake Watershed, diking and increased rainfall caused by climate change,” explains Chaffee.

Despite being threatened with legal action for not following government protocol, Chief Evelyn Joe led her community to begin filling the land with sandbags to protect the community, including a relocated cemetery, from flooding rivers. “She went up to the top of the road, and waited for the RCMP to come while the first trucks came down to fill these lands,” explains Chaffee with conviction. His mother’s legacy is one of the reasons he has continued to advocate for the protection of slakəyánc.

Members of the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation, whose name means “Red Fish Up the River,” have inhabited the ancestral lands for at least 10,000 years, since the last ice age and long before colonization, according to archaeology findings. It is believed they are one of the first communities to create a home in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland area, surviving off the abundant salmon the river offered.

In the mid-1800s, under the Indian Act, traditional territory was stolen, and the community was uprooted and relocated to slakəyánc (Coquitlam I.R. 1) and setɬamékmən (Coquitlam I.R. 2). The reallocated reserves represented a greatly reduced portion of the nation’s original land. In 1892 the first dam on the local river was built by European settlers.

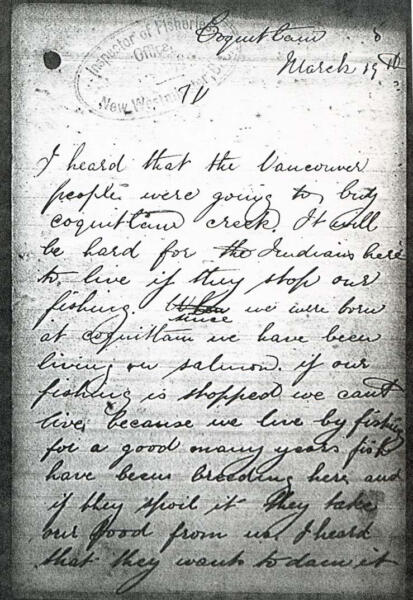

An excerpt from a letter sent in 1899 by Chief Johnnie, Kwikwetlem Nation to the federal government’s Inspector of Fisheries for British Columbia reads,

“We … would like to be given a chance to live honestly and comfortably. If the Creek is taken away from us it will be very hard for us. It is like a man taken [sic, taking] the food out of my cupboard – the creek is our store house…”

Later, in the early 20th Century, the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm community was left unprotected by diking infrastructure built to safeguard a neighboring regional park. Dikes were constructed around settler properties and recreational areas, and the dike placement funneled waters towards the reserve, causing continuous flooding. Members of the community were shot should they try to leave the reserve as it flooded.

Since 1909, the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm community has flooded at least 21 times from winter flooding on the Coquitlam River, an 18 km local river, and freshet flooding on the Fraser River, British Columbia’s longest river at 1,375 kilometers. For centuries the Nation has been forced to evolve as urban development, climate change and changing waterways have threatened access, livability and the safety of the community. Members of the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm community still live in constant fear of flooding.

After years of advocacy, work, reconciliation efforts and slow progress, in August 2024, kʷikʷəƛ̓əm announced a joint investment of more than $19.9 million from the Canada’s federal and provincial governments, the City of Coquitlam and their own contribution. Funding for the Joint Flood Mitigation Project will provide diking infrastructure improvements and flood prevention measures along the Coquitlam and Fraser Rivers over the next six years.

“Our community of slakəyánc has faced significant flood risks for so long,” shares Councillor John Peters, responsible for Emergency Management at kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation. “This funding support is essential to protect our community from the growing risks of flooding. Investing in climate adaptation is crucial to safeguarding our people and the lands we have cared for since time immemorial. It’s important our past and historical grievances have been acknowledged. We will never forget members of our community that fought so hard to get us where we are today. You need truth to heal. This new way of working together is the start of the healing journey.”

Funding will allow the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation to work collaboratively with local government organizations to upgrade the area’s existing flood protection network and construct enhanced dikes, raising portions of the existing dike by two meters. The project will also strengthen fish habitat and support water connectivity through the dike and local drainage system. New dikes and infrastructure will allow the community to look ahead knowing they are protected. They can then begin restoring sacred sites, local waterways and ecosystems.

“With this funding and the substantial improvements that will result from this project, we are working to ensure that historical wrongs are finally addressed,” says Chaffee. This joint funding announcement is the first of its kind for both the Nation and the various levels of government. The kʷikʷəƛ̓əm community sees it as an act of both Truth and Reconciliation as current local government leaders acknowledge the wrongdoing of past governments. In addition to protecting the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation lands, dike improvements will strengthen the relationships with the City of Coquitlam, fostering slakəyánc community resilience.”

“This action is a step towards true reconciliation,” adds Peters. “For the first time in history, we have felt our challenges have been heard and recognized throughout the approach to this project. We are finally doing it right and working together to protect land we share.”

Canada’s federal government is investing $11,487,350 in the flood mitigation project through the Green Infrastructure Stream of the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program. The Government of British Columbia is investing $4,827,684, kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation is contributing $992,966, and local government, the City of Coquitlam is contributing $2,670,000. The project is expected to take six years to complete and will be carried out collaboratively between the Nation and local government, the City of Coquitlam.

“My mother, and my grandmother before her have gone down in history as some of the greatest women in our community,” says Chaffee. “My aim is to ensure knowledge, wisdom and determination continue to be shared with younger members of this nation. Our elders don’t show us how to move mountains, they teach us to move mountains.”

“The past is past,” adds Peters. “What is important is what is happening now. Together, we are building a safer and more resilient future for everyone. Nautsa’mawt: One heart, one mind.”