Breast cancer awareness deserves more than pink ribbons once a year.

October ends, and with it, the flood of pink ribbons fades. The walks are walked. The bells are rung. The awareness month concludes. But for those who have navigated breast cancer, there is no ending. No month that contains the entirety of what their bodies have endured, what their minds still carry, what their futures now hold.

This is why I’m writing this in November, intentionally beyond Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Because survivorship doesn’t fit into thirty-one days, and neither should our witness of it.

Three Women, Three Truths

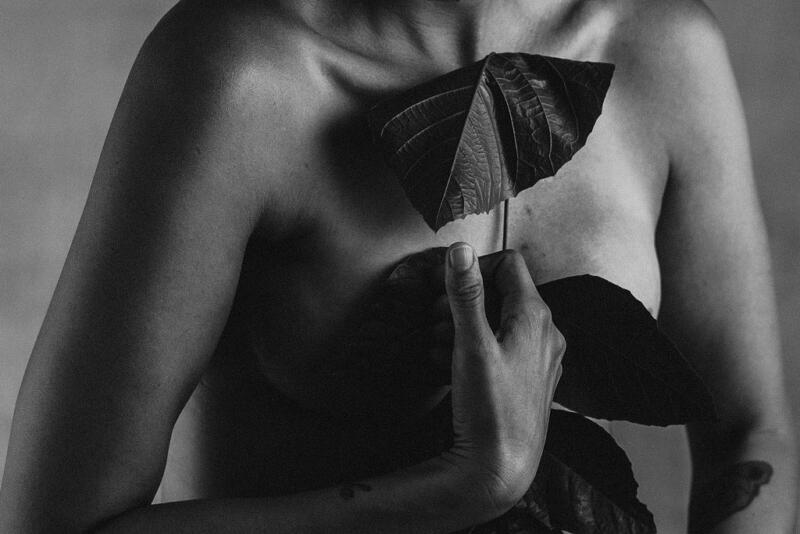

Over the past few years, I have had women come to me for photoshoots during or after their breast cancer treatment; 3 in particular all said some version of the same thing: “I don’t want the typical breast cancer photoshoot.”They didn’t want pink ribbons. They didn’t want soft, filtered light that made everything look gentle and resolved. They didn’t want to be photographed as pretty in pink “cancer survivors”, a label that, though the survivor part is true, is often used to tell stories that do not feel in alignment.

The first woman told me she felt like a badass warrior, but not the kind you see in movies. “I’ve been tired and scared but I am still here and I want to see the fire in me shine through these photos,” she said. “The fight and the fear I hold in my heart, those will be forever part of me, and while it may be uncomfortable to see, I want to see all of me.”

The second woman had rung the bell years ago but it still felt like yesterday for her. Ringing the bell is that ceremonial moment hospitals provide when treatment ends, when you’re declared “cancer-free.” She stood in my studio and said something that stopped me cold: “Everyone kept congratulating me like I crossed a finish line. But I’ll never be cancer-free. Not really. The fear is forever now.”

The third woman came to me shortly after reconstruction. She wanted to mark what her body had survived, with her scars still raw and unhealed — and she was still waiting to start her chemotherapy treatment. While she wanted to document where she was at this moment, she also knew this would be hard to witness for herself. She wanted to be seen as more than her chest, more than her scars, more than her diagnosis. “I’m still me,” she said simply. “I want that in the photos. All of me.”

The Gap Between Awareness and Witness

If you do a quick Google search for “breast cancer photoshoot” you will be flooded with a sea of pink on your screen. Pink backgrounds, pink clothing, pink ribbons tied in bows to pink flowers – SO MUCH PINK! The imagery will be soft, feminine, unified in its aesthetic. And for some, this resonates. But for many others, like the women who have come to me to create photos of them, this narrow visual representation of breast cancer erases more than it reveals.

Where is the rage? Where is the bone-deep exhaustion? Where is the terror that lives alongside the triumph? Where is the person underneath the diagnosis?

The pink ribbon has become a symbol for breast cancer awareness, and in many ways, it has done its intended job of raising funds, building community, and driving research. But it has also created a visual monoculture, one that can flatten the lived experience of survivorship into something palatable, marketable, and ultimately incomplete. It echoes that to be a woman is to be drenched in pink, which is problematic on another level.

Why This Work Matters to Me

I lost my mother to breast cancer in 2006. She was 49 years old.

For years before her diagnosis, she complained of symptoms. For years, her doctors dismissed her concerns as mental health issues. By the time they finally listened, by the time they finally looked, the cancer had already taken hold. Her battle was swift, brutal, and should never have happened the way it did.

She deserved to be heard. She deserved to be seen as a whole person, not reduced to a psychiatric label when her body was screaming for help.

Last year, they found something in my own breast tissue. The fear that flooded my body in that moment wasn’t new; it’s a fear I’ve carried since I was young, since I watched my mother die, since I understood that her cells might live in me too. The waiting, the testing, the hyperawareness of every sensation in my chest. I’m okay. The results came back clear. But that fear? It doesn’t leave. It lives in me the same way it lives in the survivors I photograph, a door in the mind that can never fully close.

Grief, I’ve learned, doesn’t resolve. It shifts, it softens, it becomes something you carry rather than something that carries you. But it doesn’t end. Just like survivorship doesn’t end. Just like the fear doesn’t end.

This is why I photograph the way I do. This is why I listen before I shoot. This is why I refuse to reduce anyone to a ribbon, a color, a single dimension of their story. Because I know what it costs when we don’t see people fully. I know what happens when we don’t listen.

This work is personal. It’s always been personal.

The Work of Witness

Photography during this era of someone’s life, and I truly believe it is a season, not a moment because as I have already shared this moment doesn’t pass quickly, requires something different than technical skill. It requires deep listening.

Understanding who they were before the diagnosis. What they love. What makes them feel powerful. What makes them feel vulnerable. Learning about the things that have nothing to do with cancer because those things still define them. The way they laugh. The books they read. The music that moves them. The people they love.

And most importantly: asking what they want these photos to say, not to others, but to themselves. What do they need to see when they look back at this time in their lives?

Sometimes they want to show their scars. Sometimes they want to cover them. Sometimes they want to be fierce, dressed in leather or draped in darkness. Sometimes they want to be soft, wrapped in natural light. There is no singular way to honor what a body has been through.

The work of a witness isn’t to impose a narrative. It’s to hold space for theirs. To create images that reflect not just their diagnosis, but their dignity. Not just their survival, but their full, complex humanity.

Beyond the Bell

In oncology, “ringing the bell” marks the end of treatment. It’s a celebration, a milestone, a moment of collective joy. But what I’ve learned from the women I’ve photographed is that the bell doesn’t signal an ending. It signals a shift, and one that still holds so much uncertainty and fear.

After the bell, there is a moment of relief. Then the hypervigilance begins. The scanning, the fear of every ache and unusual sensation. The waiting rooms and follow-up appointments become annual routines. The knowledge that your body, once something you might have taken for granted, is now something you must constantly monitor, question, and proceed with caution.

One client described it as living with a door in her mind that she can never fully close. Behind it is the possibility of recurrence. Most days, she doesn’t open it. But she always knows it’s there, and is always waiting for the knock to happen.

This is the part that doesn’t fit neatly into Breast Cancer Awareness Month. The part that isn’t resolved by the end of October. The part that lives in the in-between, between sick and well, between fear and hope, between the person you were and the person this has made you.

A Call to See Differently

To be truly committed to “awareness,” we must expand what we’re willing to see, and how. We must move beyond the sanitized, the marketed, the color-coordinated version of survivorship and into the messy, unresolved, multidimensional truth of it.

We must see survivors not as symbols of inspiration, but as whole people navigating an experience that is often terrifying, sometimes isolating, and more complex than a pink ribbon can convey.

We must acknowledge that “strength” is not the absence of fear, but the act of continuing alongside it. That survivorship is not a triumphant ending marked by a pink ribbon tattoo, but a daily practice of showing up for a body and a life that have been fundamentally altered.

And we must offer space — visual, emotional, narrative space — for people to define their own experience, in their own words, in their own time.

What You Can Do

For those supporting someone with breast cancer:

- Ask them how they want to mark this time, rather than assuming what will feel meaningful

- Understand that “cancer-free” doesn’t mean fear-free

- See them as the full person they are, not just as someone with cancer

For photographers and visual storytellers:

- Listen before you shoot

- Make space for complexity, not just inspiration

- Let your subjects lead the narrative

For anyone touched by breast cancer:

- Your story is yours to tell, or not tell, on your terms

- There is no “right” way to look like a survivor

- Your wholeness matters more than your usefulness as inspiration

Creating Images of Wholeness

As a photographer, I’ve been privileged to hold space for women as they navigate this journey, something I wish I could have offered my mother. Each session begins the same way, not with lighting setups or posing directions, but with conversation. With listening. With understanding who they are beyond their diagnosis.

The images we created together sit in my archive now, anonymous by their choice, powerful by design. In them, you see hands scarred and strong. Eyes that hold both grief and fire. Bodies that have been cut open and stitched back together, standing in defiance of the odds. Faces turned toward light, even while shadows remain.

These are not pink ribbon photos. These are photos of people who have stared down mortality and are still here, still complex, still becoming.

I am grateful to have been trusted in this way to share these experiences and to show that if pink is not your thing, you are not alone. You can reach me and explore more of my projects and photography at http://mateusstudios.com.

Every story matters. Every body deserves to be seen whole. Every month is the right time to witness that truth.