Quietly Blue: Water, Plastics, and Gently Changing Lives

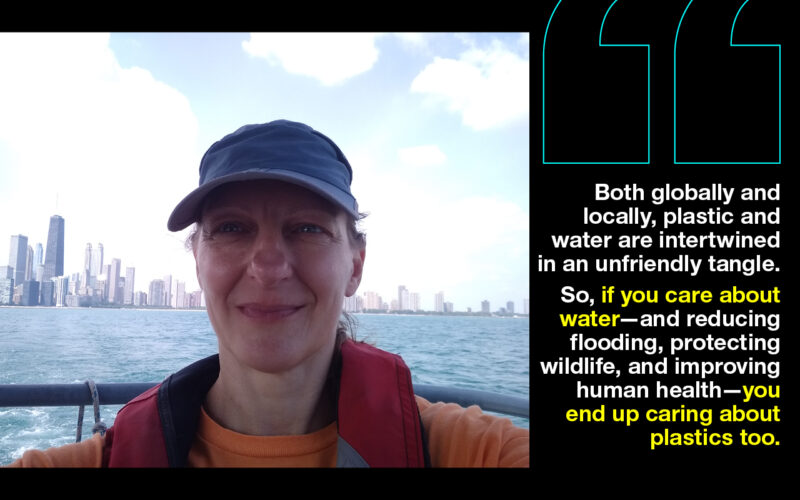

Rebecca Fiala is a gardener, a dancer, and a poet. For such an artsy person, she has a rather button-down-shirt job: she serves as a medical editor in the Department of Medical Education at the University of Illinois Chicago. She says she likes that her job involves helping people “sound more like themselves” when they’re writing. She lives with a tortoise and a cat in a house with a yard alongside a creek called Salt.

Living by Salt Creek has changed Rebecca’s life. And, quietly, Rebecca has changed Salt Creek’s life. One of the chief players in their relationship is plastic. Let me explain.

First, Salt Creek is more than a burbling backyard water feature. It tends to go a little wild, flooding yards and wearing away at human-made structures. This year, Rebecca had to replace her home’s wooden support columns with steel columns (a pricey fix), as the creek was soaking the beams too often.

Getting to know her creek and its powers and moods has moved Rebecca to understand it better. Like human history, understanding what affects one stretch of creek requires zooming out to view an entire watershed. “Where has the water been before it runs through my backyard?” she asks.

I respect Rebecca’s practical agency. She doesn’t just stand in her grass with her hands on her hips, griping about another year of record floods. Instead, she’s educated herself about what her creek has been through, and she’s allowed her life to change in response.

To zoom out from her creek to her watershed, Rebecca joined the Salt Creek Watershed Network and, through them, the—*deep breath*—the Stickney Water Reclamation Plant Community Partnership Council of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) of Greater Chicago. Essentially, she advocates locally for her community’s waterways.

The Stickney plant is one of the world’s largest, a subject of study and winner of awards as it treats wastewater and tries to manage stormwater (i.e., reduce flooding) in the Chicago area. For an entertaining introduction, learn “where pee, poop, and toilet paper go” in an MWRD video for kids. You can also read their endearingly named newsletter, For the Love of Water (FLOW).

Now, I claimed that a major player in Rebecca’s relationship with Salt Creek is plastic, and so far we’ve just talked about water. The thing is, both globally and locally, plastic and water are intertwined in an unfriendly tangle. So, if you care about water—and reducing flooding, protecting wildlife, and improving human health—you end up caring about plastics too.

When plastic bottles and other containers end up in the waterways, they clog drains, block flow, and force the water to find another way around. Often, as we’ve all seen, the water simply backs up into a wide queue as it waits for the chance to drain into its planned route.

Aside from messing up flow, plastics present another problem. Even when they finally degrade, they remain alien to the environment. They break down into microplastics, small enough to soak into the human bloodstream.

Scientists have begun detecting and tracking the buildup of microplastics in the human brain, which has increased exponentially since plastics became part of our daily lives a few decades ago. Suspiciously, the buildup is worse in patients with dementia. No direct links have been drawn; we don’t yet know how microplastics are affecting us. Until we do, keeping plastics out of the water is purely common preventive sense.

Volunteering with Salt Creek Watershed Network includes periodic cleanup days. Rebecca is on the boat crew, which she says is pretty fun. They pull out thousands of yards of trash every year, including plastic containers, tires, and fishing tackle. She’s developed her own method for safely gathering in fishing debris without hooking herself—it involves repurposing plastic bottles, wouldn’t you know.

Rebecca has seen firsthand how plastic debris clogs drains and messes up the flow of waterways. Among other inseparable influences, such as changing rainfall patterns related to global warming, plastics have a lot to do with the flooding in her backyard.

An additional reality motivates Rebecca to clean up, recycle, and reduce use of plastics: anything she uses may end up in the local waterways—once they leave her trash or recycling bin, she has no say over where they go. And, as she readily pointed out, anything in Salt Creek that floats past her yard goes downstream and affects her neighbors.

When she asks herself, “And who is my neighbor?” Rebecca’s mind’s eye follows the water from her creek to where it drains into the Des Plaines River, to the Illinois River, to the Mississippi, to the Gulf of Mexico. Her neighbors are all the people along that path—someone whose backyard looks over the Des Plaines, someone who fishes in the Mississippi, someone who wades in the Gulf.

From her poetry, I know that Rebecca holds a reverent idea of ownership—that the land and water belong both to no one and to everyone, and that the European insistence on private ownership has done great harm to the humans who lived here first. Her notion of neighbor guides her to a careful approach to her time and use of resources.

All that said, Rebecca is not one of those people who makes you feel guilty for being normal. She is highly pragmatic, as most editors are. (“If you don’t need that sentence, take it out! Down with the verbal clutter!”) When we talked about her views on recycling and reducing our use of plastics, she was quick to remind me that not everybody can afford to replace cheap plastic products with “green” ones. But even the least resourced of us can make small changes.

SIMPLE, PRACTICAL IDEAS FROM REBECCA:

Get involved in local water cleanup—“the best way to reach into the future is to keep it local,” she says.

Take a tour of a recycling plant, so you can see what is used and how.

Look for replacements for plastics you use regularly. Reducing is far more sure-fire than recycling. For instance, Rebecca is trying out no-waste shampoo capsules—“After,” she mildly complained, “I use up the four or five shampoo bottles my mom was going to get rid of.”