The Fight for Inclusive Kids Books

Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time in bookstores. In nearly all of the stores that I’ve visited, there is a section dedicated to pride or lgbtq+ characters. Even the kids’ sections have their own Pride collections. Titles like Ru Paul from the Little People Big Dreams series, Pride Puppy by Robin Stevenson, or Pink is for Boys by Robb Pearlman can be seen on displays beneath rainbow-coloured signage. As a gay author of children’s books myself, it always brings me a bit of joy whenever I walk into a store and see this.

It shows that books like this resonate with people, and that they make a difference in kids’ lives. I think it would have made a big difference in my own life if I’d had access to books that featured lgbtq+ representation. Growing up in the 80’s and early 90’s, there weren’t a lot of options, and unless you went to a niche-interest bookstore, you weren’t likely to see those books on display.

That’s not to say that there weren’t any books featuring queer characters. A few early examples come to mind, like Heather Has Two Mommies by Lesléa Newman (1989), and When Megan Went Away (1979). Not only were these books groundbreaking, they were also controversial. In 1997, Newman’s later published Belinda’s Bouquet was banned in School District 36 in Surrey, British Columbia alongside One Dad, Two Dads, Brown Dad, Blue Dads, by Johnny Valentine.

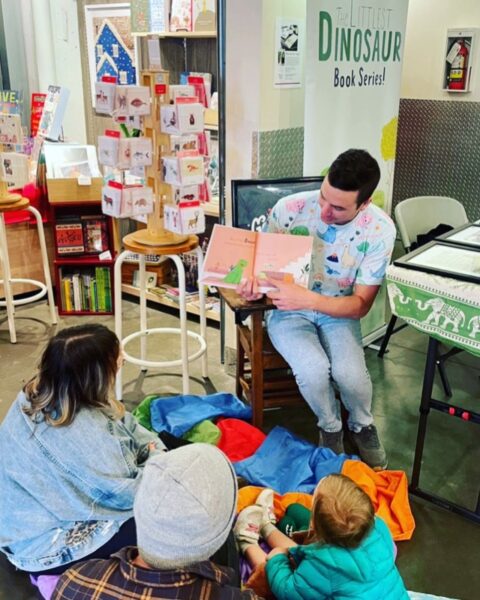

More than forty years after the publication of When Megan Went Away, we’re still seeing controversy arise out of the children’s literary spectrum. It’s why I avoid the comments sections on social media posts that have anything to do with the lgbtq+ community. Discrimination against our community isn’t anything new, but in recent years, that discrimination has been more singularly focused on the children’s literature spectrum. Inclusive books, “own voices,” authors, and even children’s storytime events like Drag Story Hour have been the targets of this kind of discrimination.

Like many in the queer community, I’ve spent a great deal of my early years being bullied and a great deal of my adulthood learning how to stand up to bullies. As a writer, the best way I knew how to stand up this time was to write. That’s why, three years ago, my boyfriend and I decided to write our own series of picture books with vibrant, positive themes of inclusion.

In The Littlest Dinosaur, Ty, a friendly tyrannosaur, is unable to find friendship because of his sharp teeth, something he was born with. The other dinosaurs are afraid of him, but Ty wants nothing more than to be loved and accepted, and he has no interest in eating the other dinosaurs. Eventually, Ty finds acceptance, friendship, and the other dinosaurs grow to accept him as well. The message is one that has resonated with our growing readership, which isn’t limited to the lgbtq+ community. There’s nothing in this story that should spark controversy.

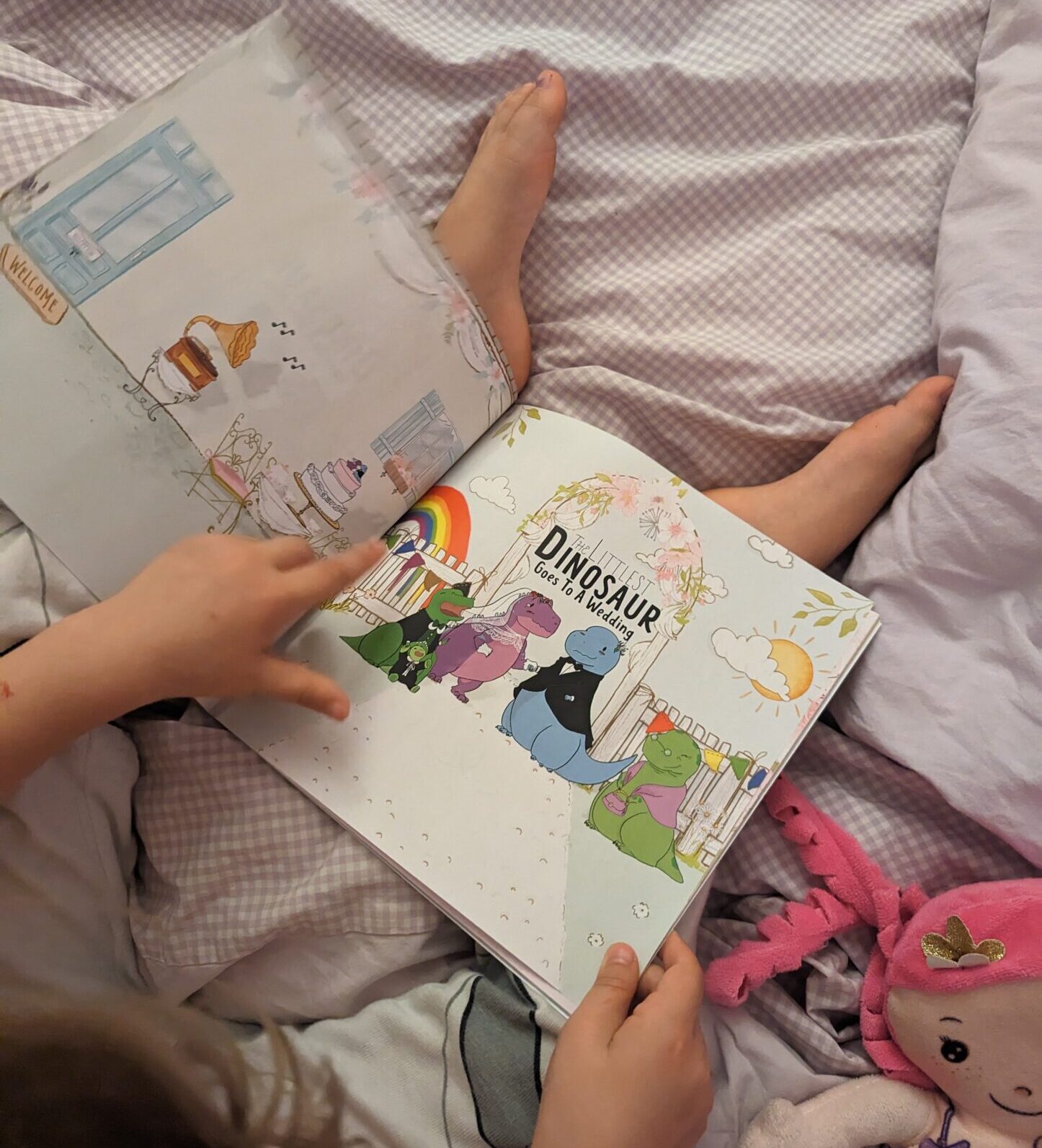

And yet, after the publication of our second book, The Littlest Dinosaur Finds A Home, which features topics like adoption, found family, and “non-traditional” families; and our sixth title, The Littlest Dinosaur Goes To A Wedding, which features the marriage of two same-sex dinosaurs, we’ve seen parents putting our books back on the shelves and directing their kids to other shelves.

The truth is, as inclusivity in children’s literature and literary events have risen to the forefront of popular culture, so has the opposition.

Books are being banned and/or challenged in schools across Canada, the United States, and around the world. Last year, calls to ban books hit the highest level ever recorded in the US, according to The Guardian. In Saskatchewan, The Ministry of Education recently announced new policies regarding parental consent to using a student’s preferred name or pronouns, as well as policies allowing parents to exclude their children from sexual health education. With many children living in situations where they would not feel safe coming out to their parents, school may be the only safe place for them. These policies, which seem to have echoes of the “Don’t Say Gay,” bill passed in Florida, which stops teachers from teaching students about lgbtq+ communities, claim to be in place to “protect the children,” but as a member of the lgbtq+ community, it sounds like the very opposite. It sounds like marginalization. It sounds like discrimination.

According to the Trevor Project, “73% of LGBTQ youth report that they had experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity at least once in their lifetime, and those who did attempted suicide at more than twice the rate of those who did not in the past year.”

I have to ask, then, if the aim is to protect children, what about children who identify as lgbtq+? How are we protecting them? By refusing to respect their chosen pronouns without forcing them to out themselves to their parents? By excluding them from sexual health education?

It seems to me that rather than protecting children, they are being caught in the middle of a political battleground between advocates both for and against LGBTQ+ representation. These culture wars are being waged in libraries, schools, and bookstores. Even in Canada, a country that outwardly claims to want to protect the rights of LGBTQ+ people, organized groups have been challenging LGBTQ+ books and protesting against drag story hour events, effectively shutting them down.

In Chilliwack, British Columbia, Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe was part of an allegation that a school library contained “concerning material.” The RCMP were called to investigate; ultimately, the claim was dismissed, as the books in question were not pornographic. To be clear, Gender Queer is a graphic memoir and not pornography, but the LGBTQ+ themes discussed in the memoir made it the most challenged book in 2022. Citing a goal of “protecting children,” such claims are being used as an attempt to censor the LGBTQ+ community.

In Manitoba, a Brandon woman recently made a similar play to have LGBTQ+ books removed from schools, claiming that these books are harmful for children, citing a need “to protect our children from sexual grooming and pedophilia.”

It’s a harmful false narrative, a suggestion that queer people (or queer books) are inherently obscene or dangerous to children. That narrative stems from a broader picture of discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. As a community, we’ve been fighting these battles for years. Back in the 1980’s, Little Sister’s Bookstore in Vancouver, BC faced book seizures by Canada Customs Officers, who prevented shipments of books they claimed were indecent. Little Sister’s fought back, entering into a legal battle that stretched out for decades. The store is still standing. So is our community.

According to Marcus McCann, a lawyer and part-owner of Toronto’s Glad Day Books – the oldest 2SLGBTQIA+ bookstore in the world – “approximately half of the most often challenged books in Canadian libraries are non-sexual LGBTQ-themed books: children’s books with queer and trans characters or themes” (2019). In 2019, eight of the ten books that made the American Library Association’s “Most Challenged Books” list featured 2SLGBTQIA+ content (Aviles).

What is it that makes people so afraid of queer people? As a gay person, it seems to me that it’s a lack of education and understanding. That’s what’s at the root of prejudice, and unfortunately, prejudice is passed down from generation to generation. That’s what makes it so important to allow children to grow up with books that teach empathy, understanding, and inclusion.

Our latest book, The Littlest Dinosaur Goes To A Wedding, includes a same-sex wedding, a right that was only recognized in Canada in 2005, less than twenty years ago.

There’s nothing harmful in this book, merely a depiction of two dinosaurs who love each other very much, and who want the best for their little ones.

Whether you’re a parent, a teacher-librarian, or have children in your life, I encourage you to support inclusive children’s literature. You might also wish to check out some of the other books mentioned in this article. If we can teach children to include those who are different from them rather than passing down generations of prejudice, we’re giving children a far better start to life.

HOW YOU CAN CREATE IMPACT:

FOLLOW author Bryce Raffle on Instagram @thelittlestdinosaurseries and other social media accounts like @itgetsbetter, a non- profit organization connecting LGBTQ+ youth for over 10 years through storytelling, education and building a global community

BUY a book from the Littlest Dinosaur Series and check out 30 Great LGBTQ+ Books for Kids and Teens

LEARN more about organizations that support LGBTQ+ Youth like The Trevor Project and Trans Lifeline

Purchase Issue 03

After a year of chaos and uncertainty, our mission for ISSUE 03 of RIPPLE OF CHANGE is to spark inspiration in our readers. There was a lot of talk of coming together, acting in solidarity for our peers, and putting others before ourselves to overcome the challenges put before us. Now, we put that to the test.

Order your copy of Issue 03 today!